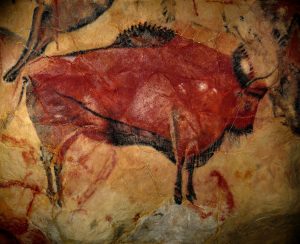

“The earliest Western art—the cave paintings in Spain and in the Dordogne valley of France—is associated with anatomically modern man, beginning about 30,000 years ago. The Cro-Magnon artists were hunters, and their drawings center on animals and the activity of the hunt.”[i] “What is our relationship with nature?” would have been their pivotal question if they could have articulated it.

“Most authorities ascribe a function of sympathetic magic to this cave art—animals were represented to increase their number or to invoke success in future hunts. Thus visual art began as an attempt to influence the future course of human activity in the natural world. If man is a tool-making animal—and if tools are man’s way to control the environment—then art was first seen as still another manual tool to subdue nature. To make a representation on a cave wall was to alter the outcome of events in time.”[ii] If that is indeed what they were doing, then we might conclude that early art manifests the power and control energy center of the false-self survival strategy. This “split” between humans and nature was the beginning of one type of existential fear, one aspect of humankind’s alienation from Simple Reality and indeed, alienation from our True self.

Superstition and illusion are joined in art. “A pictorial convention is, of course, arbitrary. Its meaning is learned; once assimilated, the convention tends to become ‘invisible,’ and we may even begin to think of it as a feature of reality itself.”[iii] In this way P-B is constructed.

“For example, most ordinary viewers expect to see a picture which suggests depth by the mechanism of linear perspective. A viewer often says that such a painting ‘looks real,’ or that it ‘looks like the way things really are.’ But such a belief is only a few hundred years old. Perspective was an innovation of the Renaissance (as we shall soon see). What is less widely recognized is that when it was first introduced, a painting in perspective looked peculiar and subjective. It certainly did not look like the way things really were.”[iv]

“Prior to that time, the use of painted space was very different. It was perfectly reasonable to show two incidents from one story in the same picture; time was not respected. It was also reasonable to show objects in space as they were known to be, and not merely as they appeared.”[v]

“The Renaissance changed all that. In perspective, a moment in time and a position in space were firmly fixed. It became illogical and ‘unscientific’ to paint in any other fashion. After centuries of familiarity, perspective has come to look real to us, in a way that Gothic or Byzantine conventions do not. But perspective is still a convention, and early Renaissance painters knew it.”[vi]

“In fact, conventions [beliefs]—since they are invisible—always serve as carriers of emotional content.”[vii] The attitudes, beliefs and values that under-gird a story like P-B and the reactions driven by that worldview can be seen in the conventions of a culture’s art. Are both artist and viewer alike not aware of this deeper content of artistic expression?

“Between observation and representation there stands a selective act, an act that requires thought. All painters are aware of it, even if their understanding is muddled. Leonardo said, ‘The painter who draws merely by eye, without any reason, is like a mirror which copies all the things placed in front of it without being conscious of their existence.’”[viii]

“There is abundant evidence for the importance of learning on simple perception. In one Swiftian experiment, it was shown that cats raised in an environment of horizontal lines would later walk into the legs of a chair; cats raised in a vertical environment would avoid the chair legs but would never jump up onto the horizontal seat.”[ix]

“In more complicated ways, what we see is related to what we have already seen. Memory can be thought of as a kind of stored perception, which we use to help us interpret new events in our world. In addition, the ability to verbalize and the ability to act are related to perception. Injuries to portions of the brain may produce a variety of disruptions in the way we respond to the visual world. A patient, given a toothbrush, may be able to identify it, but not to use it—or to use it, but not state its name—or to hear the word ‘toothbrush’ and describe the article, but not recognize it when shown, and so on.”[x]

In a similar way, the beliefs, attitudes and values stored in our brain and expressed in our behavior are hard to change and confine us via our memory to an impoverished worldview, identity and experience. A process of re-learning is necessary. The Simple Reality project is designed to guide that process.

Why do we find it difficult to grasp and experience Simple Reality? “The need for continuity in interpreting our sensory world is met at the expense of divergent or contradictory information which we ignore—which we will often fight hard not to see. But there must always be a considerable tension in our perceptual apparatus, a tension that comes from the awareness, at some level, of what we are consciously ignoring. From time to time, that tension can be collapsed, and in a moment of surprise we become aware of what has been ignored.”[xi]

What is the value of a profound context like P-A? “Thus a recognizable context improves perception by invoking a set of anticipations, a set of expectations, which sharpens our focus … Context is thus a powerful tool for sharpening our comprehension of the environment, by allowing us to anticipate what is to come.”[xii] Hence, a profound context causes a more profound perception and makes possible more profound, wholesome behaviors.

We can see in the evolution of painting a gradual human awakening. The artist does not usually consciously understand that his work exemplifies a shifting awareness any more than does, say, a physicist. “Renaissance space turned the picture frame into a window, through which one looked onto an imagined scene. The position of the observer was fixed. The painting told him where he stood—and he stood outside, looking in. The Renaissance spectator was not a participator in the picture, but a passive watcher. He did not influence the picture; he did not interact with it. The artist painted, and the observer looked on.”

“For the next four hundred years, the position of the observer remained essentially unchanged. Post-Renaissance artists bent and modified spatial conventions, without departing from the Renaissance ideal that the painter should represent what is actually seen. They used light and shadow, tone and color to expand their possibilities in depicting the visual world. There was never any real break with Renaissance conventions; Leonardo’s notebooks contain many ideas which were still being explored by the Impressionists several centuries later. The ideal of the objective observer was never questioned.”

“Dissatisfactions began to appear after 1860, and they can be seen in new spatial conventions. Edouard Manet caused his paintings to be flat; Paul Cezanne introduced distorted, ‘peripheral’ perspective as an ordinary feature of his work. As we will see later, these changes are best explained as an insight into the nature of representation, but they certainly paralleled a new scientific uncertainty about ‘objective reality.’”

“A break-point comes in the early twentieth century. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’ Avignon was painted in 1907, two years after Einstein’s special relativity theory, and the painting can be considered the first document of Cubism.”[xiii] In science we have seen a parallel shift in the evolution of the relationship between the scientist as observer or experimenter and form or “results” as outlined in Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle.

“Cubism is a conceptual art, which does not pretend any longer to reproduce the world as we see it. If Guillaume Apollinaire speaks for the Cubists, then the link between scientific advances and painting conventions is made explicit in 1913: ‘Today, the scientists do not confine themselves to the three dimensions of Euclidean geometry. Naturally and by intuition the painters were also led to the point where they concern themselves with new means of extension.’”[xiv]

“Cubism did not destroy perspective, it merely multiplied it. But by doing so, it displaced the observer from his comfortable, fixed position. It was no longer so easy to enter the picture through the canvas window; the question of the artist’s intent, the difficulty of following his vision, became barriers. The fact that the picture was only a representation of reality—a trace remaining of the artist’s own complex vision—was all too obvious.”[xv] What we can and indeed must learn from this is the disturbing limitation of our senses when it comes to representing reality.

“Just as physicists were discovering that their fields of inquiry had more to do with themselves than with any objective reality, so artists were increasingly devoted to the idea of art as a self-contained system with no referents outside itself. The proper subject of art became the artist and his actions.”[xvi]

“Similarly, the trend toward increasing abstraction was inevitable. [In painting this was the intuitive struggle to detach from the world of delusional form.] In his search for purer self-expression, the artist abandoned distracting elements, until finally representation itself—a recognizable image—was eliminated as unnecessary to the proper functioning of the artist.”[xvii]

“Before an Abstract Expressionist painting, the objective observer—the Renaissance witness—cannot function at all. In a real sense, the observer is no longer the audience but the artist himself. As in physics, the observer and the observed are inextricably linked. And as in physics, this linkage produces a language of personal, internal reference which the outsider finds obscure and forbidding.”[xviii] The goal, whether consciously understood or not, is not complete abstraction but pure “feeling” which can be expressed in any way the artist wishes without conforming to a pre-determined method or any artificial standard.

“But just as physics would come to a standstill if there were no fresh experiments—new inquiries into the physical world—to ponder and explain, so art would cease to function if it divorced itself entirely from the perceptual world. From this point of view, complete abstraction represents a kind of limiting case for art; it cannot exist except in opposition to a tradition of representational art.”[xix] The goal of art never has been complete abstraction but as with all human expression the goal is to attain the present moment and the experience of “feeling.” All of us can naturally express beauty in any way we wish without conforming to a predetermined method, style, tradition or artificial critical standard.

In fact, we cannot know what objective reality is since the intellect and senses were not designed to achieve that realization. Our intuition, an expression of our inner wisdom, however, is capable of very profound realizations and insights.

As author Michael Crichton put it in speaking of the work of artist Jasper Johns: He had a “strong sense of acceptance of things as they are [the ability to respond]—surely an undercurrent in his willingness to use pre-existing imagery and objects.”[xx]

[i] Crichton, Michael. Jasper Johns. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1977, page 80.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid., page 81.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid., page 82.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid., page 85.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid., page 86.

[xii] Ibid., pages 86-87.

[xiii] Ibid., page 78.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid., pages 78-79.

[xvii] Ibid., page 79.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid., page 63.

____________________________________________________________

Find a much more in-depth discussion in books by Roy Charles Henry.