We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.

We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.

John Winthrop

Americans, let’s be clear from the outset, your false self may be salivating at the prospect of discovering you are special—so-called American exceptionalism. Forget it! It ain’t gonna happen because there is no evidence for it and swallowing that bunk in the first place is like gulping down hemlock. Let’s try something “novel” called the truth.

It might be interesting, since professional historians are mesmerized by the P-B story, to see what writers of fiction would reveal about the fantasy that many Americans believe to be objective truth. Since the majority of Americans profess to be Christians of one sort or another, how well are we doing with “love they neighbor as thyself” and “love God with all thy heart, soul and mind.”

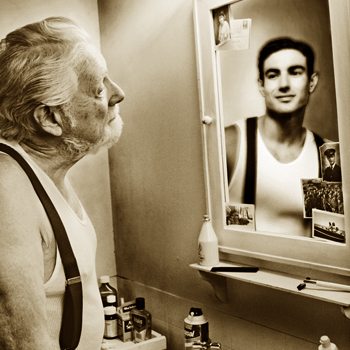

Now, for those of you who are still with us, your courage will be well rewarded; you will find out who you are and more importantly, who you are not. In the prose and poetry of American writers we will trace the evolution of the American false self with the occasional fleeting glimpse of the True self. Notice the key role that the American narrative plays in determining our shifting identity and, of course, the influence of both in explaining the unique behavior of Americans which turns out to be not so exceptional after all or at least, not in the way many of us might like to imagine.

In the beginning, of course, our identity was that of British subjects with the craving of our false-self security center salivating at the thought of opportunity in the New World. John Winthrop, who would later become the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony looked across the pond and saw opportunity. “Why then should we stand striving here for places of habitation … & in the meantime suffer a whole Continent as fruitful & convenient for the use of men to lie waste without any improvement.” How nice! Our earliest ancestors had the intention of “improving” upon the creation of Mother Nature. Axe in hand, off they went to “lay waste” to the whole continent, far beyond anything John Winthrop could have imagined. If by American exceptionalism we mean exceptionally destructive, we have indeed proved to be exceptional.

Only the best people came from the old sod, at least according to William Stougton who would later become a judge in the Salem witchcraft trials. “God sifted a whole nation that He might send choice grain over into this wilderness.” Maybe this attitude was the beginning of the idea of exceptionalism. “Choice grain?” You be the judge.

As we might expect, our ancestors were not free of the illusion of the other and the tragic results of that delusion. William Bradford of Plymouth Plantation expressed the belief common among his shipmates on the Mayflower. “Being thus passed the vast ocean and a sea of troubles … they now had no friends to welcome them, nor inns to entertain or refresh their weather-beaten bodies, no houses or much less towns to repair to, to seek for succor. [The] savage barbarians [who greeted them, he continued] were readier to fill their sides full of arrows than otherwise.” But as H. L. Mencken would later humorously observe, the colonists were not the put upon “innocents.”

When the Pilgrim Fathers landed, they fell upon their knees—and then upon the aborigines.

H. L. Mencken

Our colonial ancestors were then exceptional in their “violent” treatment of both nature and the American aborigines. We must also remember that these early New England settlers were Calvinists with a rather dark, if not ghastly worldview. Like most of his contemporaries, the poet Michael Wigglesworth wrote a long theological poem, the title of which revealed what was often on his mind. The following excerpt is from his The Day of Doom: A Poetical Description of the Great and Last Judgment.

Before his face the heav’ns give place,

and skies are rent asunder,

With mighty voice, and hideous noise,

more terrible than thunder.

In writing about the popularity of The Day of Doom many years later (after Calvinism was passing from Yankee New England), James Russell Lowell probably had a good laugh when he cynically observed that it “was the solace of every fireside, the flicker of pine-knots by which it was conned perhaps adding a livelier relish to its premonition of eternal combustion.” Yes, the identity of many early New England settlers was that of being a “sinner,” that is to say, exceptionally wicked.

As we read a portion of a sermon by the Reverend Jonathan Edwards, the prophet of the “Great Awakening” (a religious movement that began in New England in 1734), we hear the narrative that gave those sitting in the pews their guilt-ridden sense of self. “The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathesome insect, over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; his wrath towards you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the fire; he is of purer eyes than to bear to have you in his sight.” That would have been enough to ruin one’s “day of rest.”

Harvard professor Sacvan Bercovitch traced the origin of America’s identity of “exceptionalism” to Puritan political and religious rhetoric. In his 1978 book The American Jeremiad “he discerned an American version of the jeremiad, a harangue [see Edward’s rhetorical style above] about society’s declining morals named after the biblical prophet Jeremiah. In this version, however, after berating an audience for its failings, the speaker would end up extolling the country as the world’s best hope for redemption.” Before we had even become America, our exceptionalism had extended to being the “Messiah” for the rest of the world, at least in the worldview of some Puritans.

We don’t want to neglect the experience of the women on the American frontier. They had more responsibility for the survival of the community than their cousins back home and some at least felt that should come with more freedom. Enter Abigail Adams, the wife of President John Adams who said adequate schooling should be extended to “every class and rank of people, down to the lowest and poorest.” We can hear Abigail saying to John, “If we mean to have heroes, statesmen, and philosophers, we should have learned women.” Indeed, and so we can add an appreciation for education to the identity of our colonial ancestors.

An appreciation for the natural beauty of the New World also was evident early on in our history. The landscape painter Thomas Cole painting the Hudson valley in the 1820s and 1830s lamented “They are cutting down all the trees in the beautiful valley on which I have looked so often with a loving eye.” As today, our materialism was in conflict early on with our sense of the good, the true and the beautiful. Our True self would wrestle with our false self throughout our history.

Poet William Cullen Bryant reminded Cole as he left for a tour of Europe to not forget the Hudson River valley they both cherished.

Gaze on them, till the tears shall dim thy sight,

But keep that earlier, wilder image bright.

In Simple Reality we have used New York City as the symbol of greed (the security energy center of the false-self survival strategy). In The New Yorker magazine in 1839, Horace Greeley takes us back to when greed was in its early stages in what was to become the “Big Apple.” But that’s not all. “New York has become the metropolis, in our country, not only of commerce but of literature and the arts. Like Tyre of old, she has covered the sea with ships, and her merchants are princes … No man well acquainted with the history of Literature and Art in our country during the last ten years, can refuse to acknowledge that New York has towered above her sister cities.”

Many of our early writers became mesmerized by the cant of the myth of American uniqueness. In 1868 John William De Forest published an essay titled “The Great American Novel” in The Nation. He thought that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin embodied the best in American idealism and promise for the future. To him America was a “populace of eager and laborious people, which takes so many newspapers, builds so many railroads, does the most business on a given capital, wages the biggest war in proportion to its population, believes in the physically impossible and does some of it.” As our earliest writers found much to praise in America, others began to look more deeply and began to see a darker side.

Another center from which the false self draws energy is that of sensation (sometimes called the affection and esteem center) which held a particular allure for Edgar Allan Poe. “I love fame—I dote on it—I idolize it. I would drink to the very dregs the glorious intoxication.” The sensation energy center is where our addictions reside. The poet Poe who also perfected the short story was intimately acquainted with the folly of self-medication. At only 40 years old, Poe was found dead drunk lying in a gutter on a Baltimore street. He died a few days later, was buried in an unmarked grave and forgotten for 26 years. Walt Whitman was the only prominent American to attend the ceremony in 1849 when the tombstone was placed upon Poe’s grave.

One never knows for sure who is a mystic and who is not but Walt Whitman’s art and behavior qualify him above all others in the flow of our history. Two others, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson studied the Bhaghavad Gita and Hindu mysticism.

While living at Walden Pond outside Concord, Thoreau was amused by Irish laborers who came into the area to cut block of ice from the ponds for shipment around the world, including India. “Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants … of Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat-Geta … I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! There I meet the servant of the Bramin … come to draw water for his master … The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.”

Thoreau understood, as did Buddha, that craving of any kind would cause suffering. A man is rich, Thoreau observed, “only in proportion to the number of things he can afford to do without.” We can appreciate in our own time, enamored as we are with our high-tech society, Thoreau’s prescient warning vis-à-vis “technological toys.” “Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys which distract our attention from serious things … We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate … As if the main object were to talk fast and not to talk sensibly. The nation itself, with all its so-called internal improvements, which by the way, are all external and superficial, an unwieldy and overgrown establishment … tripped up by its own traps.”

Emerson started his career as a Unitarian minister only to abandon it when he realized that all religions were too constricting. “It is the best part of the man that revolts from official goodness … Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist.” In 1838 he delivered an address at the Harvard Divinity School and surprised the audience when “he attacked all formal religion and championed intuitive spiritual experience.”

Unlike many WASPS (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants) Emerson welcomed immigrants realizing that diversity would give the nation a more resilient identity. “The energy of Irish, Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Cossacks, and all the European tribes—and of the Africans, and of the Polynesians—will construct a new race, a new religion, a new state, a new literature, which will be as vigorous as the new Europe which came out of the smelting pot of the Dark Ages.”

And now back to Whitman. “An American bard at last! One of the roughs, large, proud, affectionate, eating, drinking, and breeding, his costume manly and free, his face sunburnt and bearded, his posture strong and erect, his voice bringing hope and prophecy to the generous races of young and old … Right and left he flings his arms, drawing men and women with undeniable love to his close embrace, loving the clasp of their hands, the touch of their neck and breasts, and the sound of their voices. All seems to burn up under his fierce affection for persons.” Not faint praise from the critic because he was the critic. This poet had to see the American exceptionalism in himself because no one else was paying attention to his poetry.

“Qualified” critics like Longfellow, Lowell, Holmes, and Mark Twain found little or nothing to praise in his Leaves of Grass. The problem was as Whitman suspected in the lingering Calvinistic prudery that had yet to take its last breath. Thoreau found several pieces in Leaves of Grass “disagreeable, to say the least; simply sensual. He does not celebrate love at all. It is as if the beasts spoke.”

Throwing myself on the sand, confronting the waves,

I, changer of pains and joys, uniter of here and hereafter.

Whitman walked the talk of compassion—the acid test of present moment awareness—response! Going to visit his younger brother in Washington who had been wounded in the Civil War he remained there for three years caring for wounded soldiers from both the North and South.

On, on I go, (open doors of time! Open hospital doors!)

The crush’d head I dress, (poor crazed hand tear not the bandage away,)

The neck of the cavalry–man with the bullet through and through I examine,

Hard the breathing rattles, quite glazed already the eye, yet life struggles hard,

(Come sweet death! Be persuaded O beautiful death!

In mercy come quickly.)

“H. G. Wells called [Stephen] Crane ‘beyond dispute, the best writer of our generation.’ The Red Badge of Courage, Wells wrote, ‘was a new thing, in a new school … entirely original and novel. To a certain extent, of course; that was the new man as … a typical young American, free at last, as no generation of American had been free before, of any regard of English criticism, comment or tradition, and applying to literary work the directness and vigor … there is Whistler even more than there is Tolstoy in The Red Badge of Courage.’” Here emerges, if Wells is correct, our next type of American exceptionalism, namely originality.

History is not strictly speaking belles lettres but historian Henry Adams had insights relevant to our theme of American identity. “His well-grounded pessimism subtly illustrated the transition of America during his mature years from an age of confidence to an age of doubt, and that, ironically, at a time the nation was reaching new peaks of material prosperity and scientific achievement.”

Adams had misgivings about the dehumanizing aspects of the American expression of the harsher aspects of the Industrial Revolution as Thoreau had earlier about the new technology associated with the Industrial Revolution. “I am wholly a stranger in it. Neither I, nor anyone else, understands it. The turning of a nebula into a star may somewhat resemble the change. All I can see is that it is one of compression, concentration, and consequent development of terrific energy, represented not by souls, but by coal and iron and steam.”

The World Columbian Exposition of 1893 held in Chicago foreshadowed the future of the America about which Adams had misgivings. The fairground was called the White City and its buildings displayed what the industrial and scientific future would look like. Carl Sandburg would later describe it as the “City of the Big Shoulders.”

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler …

Laughing the stormy, husky, brawling laughter of Youth …

Sandburg was not afraid to look at the particularly harsh reality of P-B emerging in such American cities as the turn-of-the-century Chicago.

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them,

for I have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys,

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer:

Yes, it is true I have seen the gunmen kill and go free to kill again

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is:

On the faces of women and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger …

In 1888, Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel, Looking Backward, or 2000-1887 expressed his doubts about the direction in which laissez-faire capitalism was starting to take the nation. “Conceived as ‘a mere literary fantasy, a fairy tale of social felicity,’ the book is actually a sharply pointed and skillfully directed exposure of the inadequacies of the private-enterprise system, of the inefficiency and material waste to which that system leads, and, worse, of the attrition of human values that results from it.”

The idealist Bellamy imagined a paradigm shift conceived on the model of earlier American utopian experiments. “The story concerns a young Bostonian who awakens in the year 2000 from a sleep of more than a century to find that his familiar world has been utterly transformed. He awakens to a futuristic Brook Farm, so to speak, organized on a national scale. Under a new system of democratic collectivism, private enterprise has been abolished; state capitalism has replaced the great business monopolies of earlier times; social injustice, crime, poverty, and warfare have been eradicated. Everything has been accomplished by orderly, democratic process. Under such benign and rational socialism, public intelligence and ethics have been raised to almost incredible heights. Man has conquered the machine, and all share equally in the abundant economy they have together helped to create.” One way in which Americans were not exceptional, is that they never seriously entertained profound paradigm shifts and indeed according to several authors and poets, seemed to be moving into a relatively darker narrative.

As Bellamy looked forward to utopia, Willa Cather saw the ideals of the hardy, pioneer spirit being replaced by the greedy predators of corporate capitalism. In her novel A Lost Lady she wrote: “The Old West had been settled by dreamers, great-hearted adventurers who were impractical to the point of magnificence; a courteous brotherhood strong in attack but weak in defense, who would conquer but not hold. Now all the vast territory they had won was to be at the mercy of men like Ivy Peters who had never dared anything, never risked anything. They would drink up the mirage, dispel the morning freshness, root out the great brooding spirit of freedom, the generous, easy life of the great landholders. The space, the colour, the princely carelessness of the pioneer they would destroy and cut up into profitable bits, as the match factory splinters up the primeval forest.”

Jack London’s The Call of the Wild is the story of a dog that becomes wild and travels with a wolf pack when taken to Alaska. Much of London’s fiction is about the underlying savagery of the false-self masked by surface appearances, attitudes, beliefs and values. “Man himself is little better than an animal. ‘Civilization has spread a veneer over the soft shelled animal known as man,’ he wrote. ‘It is a very thin veneer … Starve him, let him miss six meals, and see gape through the veneer the hungry maw of the animal beneath. Get behind him and the female of his kind upon whom his mating instinct is bend, and see his eyes blaze like an angry cat’s, hear in his throat the scream of wild stallions, and watch his fist clench like an oran-outang’s … Touch his silly vanity, which he exults into high-sounding pride, call him a liar, and behold the red animal in him that makes a hand clutching that is quick like the tensing of a tiger’s claw, or an eagle’s talon, incarnate with desire to rip and destroy.’”

Edith Wharton was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for The Age of Innocence (1920). She had been born into the leisure class of the vanishing Knickerbocker society of New York. Like Jack London, she saw beneath the veneer of the socially acceptable false self of those people “who dreaded scandal more than disease, who placed decency above courage, and who considered that nothing was more ill-bred than scenes except the behavior of those who gave rise to them.”

Another writer who saw that all was not well with the identity that Americans were choosing to perpetuate was Theodore Dreiser. He published the aptly titled An American Tragedy in 1925. “Dreiser saw the ruthlessness and the amorality of the world as aspects of a fundamental natural law that inexorably dictated the lives of men and women. There was in nature, he wrote, ‘no such thing as the right to do, or the right not to do. We suffer for our temperaments which we did not make, and for our weaknesses and lacks, which are not part of our willing or doing.’” What is now being articulated by American authors is the exceptionalism of unconsciousness, not, of course unique to Americans.

Some say Robert Frost was the most beloved American poet of the 20th century. In his poem “Fire and Ice” he revealed his acquaintance with his own false self.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Frost intuited that human suffering had its origin in resistance to life as it is but was perhaps too optimistic in assuming that his fellow Americans would embrace the gift of life they had been given. The following is a portion of his poem “The Gift Outright.”

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

Frost later regressed in his own personal identity away from feeling at one with nature toward his delusional false self. “In his earlier poems he describes the sometimes uneasy but always meaningful relation of man to nature. Man has need of nature, but nature has no need of man. Later he came to view the indifference of nature more as a hostile force with which man must struggle as heroically as he can. He regarded man in his earthly predicament with a detachment that ruled out any degree of compassion.” Americans proved exceptional in failing to trust their own intuition, their inner wisdom.

John Dos Passos, in his trilogy of related novels, U.S.A. (1938), chronicled the American experience through most of the Depression years. “It is a tract of the times more than it is a timeless testament. It is a very sad epic that concludes in a massive indictment of American society. In his panoramic view Dos Passos saw American life only in terms of futility and frustration, corruption, and defeat for the individual, beyond hope of redemption by the most radical measures.” In his fiction, Dos Passos weaves incisive biographies of key Americans. He has labor leader Eugene Debs advocating self-reliance, bringing us full circle back to Emerson.

“I am not a labor leader. I don’t want you to follow me or anyone else. If you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of the capitalist wilderness you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into this promised land if I could, because if I lead you in, someone else would lead you out.”

The Waste Land (1922), T. S. Eliot’s most famous poem, describes the postwar world as a desolate, sterile and chaotic place, one of the most striking depictions of P-B. The “Waste Land” is “an ‘immense panorama of futility and anarchy’ whose inhabitants are spiritually barren and desperate. Life is devoid of value.”

In his post-World War II essay, “The White Negro,” Norman Mailer portrays an American identity traumatized by the horrors of concentration camps and the threat of the atomic bomb. “No wonder then that these have been the years of conformity and depression. A stench of fear has come out of every pore of American life, and we suffer from a collective failure of nerve. The only courage, with rare exceptions, that we have been witness to, has been the isolated courage of isolated people.”

Multidisciplinary artist Claudia Rankine manages in her work to look without blinking at the reality of the human condition, especially in America, her suffering homeland. The following is from her latest book (2014) Citizen. “The world is wrong. You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you; it’s burned into your flesh, into its own cupboard. Not everything remembered is useful but it all comes from the world to be stored in you … Did I hear what I think I heard? Did that just come out of my mouth, his mouth, your mouth?”

Well yes, Freudian slips can betray the bigotry and the fear of the false self. The other forever haunts our delusional identity. Rankine, who is African American, shines the light of truth on the darkest and seemingly never-ending chapter of American history. Why does this cancer seem so difficult to remove from our infected community? Simple Reality explains not only the resilience of this behavior but the treatment that would cure the patient.

In the mean time we must use every means at our disposal in our search for Truth, and our great writers make their contribution to that quest. The courage to write the truth after having the insights that reveal that truth is not common even in our best novelists and poets. For example, J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye “is at heart a naively passionate indictment of American phoniness and fallenness.”

In his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, William Faulkner expressed his fear of the nuclear age and that bellicose aspect of the false self. And yet, he transcended that illusion and acknowledged the indestructible True self. “There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? I believe that man will not merely endure: He will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.” There you have it at long last, our true identity and there is nothing exceptional about it, it is universal.

_________________________________________________________

References and notes are available for this essay.

Find a much more in-depth discussion in the Simple Reality Trilogy

Where Am I? Story – The First Great Question

Who Am I? Identity – The Second Great Question

Why Am I Here? Behavior – The Third Great Question

Science & Philosophy: The Failure of Reason in the Human Community