Art and

Consciousness

In this book, works of art are cited as examples of the principles or ideas being discussed. The reader is encouraged to view the works of art online.

The souls of 500 Sir Isaac Newtons would go to the

making up of a Shakespeare or a Milton.

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1801)

Art and Consciousness

The Romans were able to create a culture by borrowing from the Greeks and adapting some of the best elements of Greek institutions to their own identity. The old narrative and the new were synthesized into a shifted paradigm better suited to, what was then, the “modern” Roman worldview. “It was typical of the Romans to take from Greek architecture what they liked, and to apply it to their own needs. They did the same in all fields.”[i]

The Roman Colosseum was built in 80 CE “On the whole it is a utilitarian structure, with three storeys of arches, one above the other, to support the seats of the vast amphitheatre inside.”[ii] The Romans built for utility first and beauty second. Architecture in this case expressed a deeply self-destructive function and no human community expressing the brutal inhumane “entertainment” that went on in the Colosseum could endure for long.

The most outstanding achievement of the Greeks was the eloquent expression of beauty. For the Romans it was roads, baths and aqueducts. One, a soulful expression—the other, a reaction to the practical demands made by the false self.

Even the adaptations in Roman art were subordinated to communicating to the people back home the successes of the far-flung campaigns that were “creating” the Roman Empire. “All the skill and achievements of centuries of Greek art were used in these feats of war reporting. The main aim was no longer that of harmony, beauty or dramatic expression.”[iii] In the lower part of Trajan’s Column we see artists performing a sort of “journalistic” function. Their artistic sensibility was subordinated to pleasing politicians.

-

- Trajan’s Column, 114 CE

As a result, when pragmatism is dominant over the artistic sensibility, beauty is lost. When intuition or the “heart” is subordinated to the intellect or “head,” then the creative process, the free, inspired art of the present moment is lost and pseudo-art is the result. “At first, artists still used the methods of storytelling that had been developed by Roman art, but gradually they came to concentrate more and more on what was essential.”[iv]

-

- The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, 520 CE

The artist in this new paradigm is serving an institution—not his own creative instincts or personal inspiration. He is no longer serving the instinctual evolutionary progress of the Implicate Order or his own True-self. Religious art, if it can be called art at all, is stiff and contrived—an expression of beauty is no longer the artist’s aim and hence, truth is lost as well. The natural evolution of art and the creative process ends.

“Artists no longer checked their formulae against reality. They no longer set out to make discoveries about how to represent a body, or how to create the illusion of depth.”[v] We see in these two illustrations how the artistic imagination was stifled by the Eastern Church:

-

- Enthroned Madonna and Child, 1200 CE

- Christ as Ruler of the Universe, the Virgin and Child, and Saints, 1190 CE

“On the other hand, the stress on tradition, and the necessity of keeping to certain permitted ways of representing Christ or the Holy Virgin, made it difficult for Byzantine artists to develop their personal gifts.”[vi]

Once a paradigm becomes dominant—as the American worldview dominates modern societies today—it can influence for better or worse the less vital cultures and their stories.

The influences of Greek and Roman art were felt even as far away as the Orient. “During the centuries after Christ, Hellenistic and Roman art completely displaced the arts of the Oriental kingdoms, even in their own strongholds. Egyptians still buried their dead as mummies, but instead of adding their likenesses in the Egyptian style, they had them painted by an artist who knew all the tricks of Greek portraiture.”[vii]

-

- Mummy Portrait of a Man, 150 CE

“The Egyptians were not the only ones to adapt the new methods of art to their religious needs. Even in far distant India, the Roman way of telling a story, and of glorifying a hero, was adopted by artists who set themselves the task of illustrating the story of peaceful conquest, the story of Buddha.”[viii]

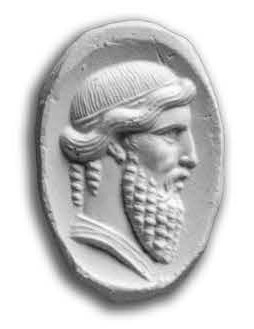

-

- Head of Buddha, 200 CE

“The humble wall-painting from the Jewish synagogue is of interest to us, because similar considerations began to influence art when the Christian religion spread from the East and also took art into its service.

-

- Moses Striking Water from the Rock, 245-256 CE

“When Christian artists were first called to represent the Savior and His apostles it was again the tradition of Greek art which came to their aid. [Christ with St. Peter] shows one of the earliest representations of Christ, from the fourth century CE. Instead of the bearded figure to which we have become accustomed through later illustrations, we see Christ in youthful beauty, enthroned between St. Peter and St. Paul, who look like dignified Greek philosophers.”[ix]

-

- Christ with St. Peter, 359 CE

Once again, as in Egypt, art was employed for religious purposes and for storytelling and loses its vitality. “Its main purpose was to remind the faithful of one of the examples of God’s mercy and power.”[x]

“These three men seen from in front, looking at the beholder, their hands raised in prayer, seem to show that mankind had begun to concern itself with other things besides earthly beauty. Few artists seemed to care much for what had been the glory of Greek art, its refinement and harmony. Sculptors no longer had the patience to work marble with a chisel, and to treat it with that delicacy and taste which had been the pride of the Greek craftsmen.”[xi]

-

- The Three Men in the Fiery Furnace, 200 CE

“To a Greek of the time of Praxiteles these works would have looked crude and barbaric. Indeed, the heads are not beautiful by any common standards.”[xii]

-

- Portrait of an Official from Aphrodisias, 400 CE

The loss of sensibility in art indicates the loss of consciousness itself and when the artist as prophet is no longer contained in a story that strives for awareness he loses his connection to truth. And as we know, truth is beauty.

Chapter 1 – Simple Reality and the Birth of Western Art

[i] Gombrich, E. H. The Story of Art. London: Phaidon Publishers Inc. 1966, page 81.

[ii] Ibid., pages 79-80.

[iii] Ibid., page 85.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid., page 97.

[vii] Ibid., pages 85-86.

[viii] Ibid., page 86.

[ix] Ibid., page 87.

[x] Ibid., page 89.

[xi] Ibid., pages 89-90.

[xii] Ibid.

__________________________________________________________

Illustrations: Gombrich, E. H. The Story of Art. London: Phaidon Publishers Inc., 1966.

- Figure 75 – The lower part of Trajan’s column, 114 C.E.

- Figure 87 – The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, 520 C.E.

- Figure 85 – Enthroned Madonna and Child, 1200 C.E.

- Figure 86 – Christ as Ruler of the Universe, the Virgin and Child, and Saints, 1190 C.E.

- Figure 76 – Portrait of a man, 150 C.E.

- Figure 77 – Head of Buddha, 200 C.E.

- Figure 79 – Moses striking water from the rock, painted between 245 and 256 C.E.

- Figure 80 – Christ with St. Peter, 359 C.E.

- Figure 81 – The Three Men in the Fiery Furnace, 200 C.E.

- Figure 82 – Portrait of an official from Aphrodisias, 400 C.E.

__________________________________________________________

Find a much more in-depth discussion in books by Roy Charles Henry.