This essay was started on October 5, 2014 and the subject was ostensibly driving cars while using cell phones and the tragedies that can result when combining these two activities. We talk a lot these days about this problem and many others with numerous insights into what to do about these many threatening and often self-destructive behaviors—but nothing happens—our behaviors remain the same. What is this paralysis in the face of irrational behavior? Are we cruel or crazy?

This essay was started on October 5, 2014 and the subject was ostensibly driving cars while using cell phones and the tragedies that can result when combining these two activities. We talk a lot these days about this problem and many others with numerous insights into what to do about these many threatening and often self-destructive behaviors—but nothing happens—our behaviors remain the same. What is this paralysis in the face of irrational behavior? Are we cruel or crazy?

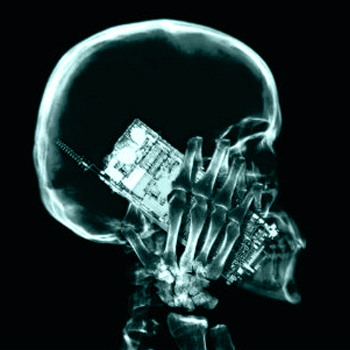

We now begin the process of broadening our inquiry by looking at what has come to be called “attention science.” Studying the intersection of technology and human behavior, also called cognitive neuroscience which began in World War II with helping pilots and radio operators from being overwhelmed by the new technology they were learning to use. Not surprisingly, operators of the devices learned what we are also aware of today, namely, pay strict attention to what you are doing, that is to say, be present.

The problem with paying attention is that we don’t want to. We invest a lot of energy in purposely distracting ourselves. Why? Well, because this is our chief strategy for avoiding suffering or in denying that our lives are dissatisfying. If we are not aware of what is really happening we can perhaps create an illusionary (made-up) story and convince ourselves that the identity determined by that story is really us, that our “new” we and our resulting “new” life is OK.

Robert Kolker reviewing Matt Richtel’s book on how and why we distract ourselves and the consequences of doing so agrees that Americans work hard to stay unconscious. “We are distracted because we want to be. Why else would they sell so many smartphones? As Richtel explains, a good gadget is essentially magical, commandeering our focus with delight and surprise and ease (Steve Jobs used the word “magical” about the iPhone when it debuted).”

In September 2006, Young Reggie Shaw, distracted while talking on his cell phone with his girlfriend, crashed into a car killing James Furfaro and Keith O’Dell. Shaw’s story is part of a 35-minute AT@T public service announcement directed by Werner Herzog released in 2013. The message of the film “From One Second to the Next,” is part of AT@T’s campaign against texting and driving. Matt Richtel won a Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles he wrote about distracted driving in The New York Times. This year (2014) Richtel’s book A Deadly Warning: A Tale of Tragedy and Redemption in the Age of Attention, includes Shaw’s story of redemption.

If Americans were immersed in the context of Simple Reality, our True selves would respond to the facts surrounding texting while driving and we would simply not use our cell phones while driving. That would be a compassionate response. But we live in P-B which effectively discourages compassion. In fact, the story that we tell ourselves encourages Americans to conceal, lie about and deny the truth. Instead of considering the suffering of our fellow human beings, a True-self response, our false-self hunkers down in a reaction of fear and self-preservation.

A community wherein genuine compassion is discouraged and self-promotion and self-protection are paramount behaviors will not long survive or at least will not be fit for human habitation. We return to the tragic events in the life of Reggie Shaw. “A fundamentally decent teenager, Shaw nevertheless had things he was ashamed of and family expectations to live up to. His pattern, even before the crash, was to dissemble [to disguise or conceal behind a false appearance—a decidedly false-self behavior] in order not to make trouble for those around him. Once the tragedy happened, Richtel writes, ‘the intensity with which the family undertook the defense had a self-perpetuating and escalating force: Reggie denied texting, the family backed him up and Reggie, never someone to let others down, dug deeper.’”

Our false-self identities determined by the P-B narrative create behaviors that escalate and intensify our suffering and so it was with Reggie Shaw. Compassion was nowhere in sight. “Should Reggie be charged with negligence or manslaughter, or nothing at all? Even if texting and driving is wrong, should he have known that? In Richtel’s sensitive account, we come face to face with the horrible Catch-22 of accident litigation that discourages one party from apologizing to another, for fear of admitting liability [enter the lawyers, exit compassion]. This apparent standoffishness helped persuade the prosecutor to make Shaw a test case for texting and driving. Which in turn caused Shaw’s family to accuse the prosecutor of waging a witch hunt. Which only appalled the victim’s widows and families and advocates even more.”

Shaw will never be able to do more than approach redemption unless he can find compassion for himself. He travels the country making speeches, a spokesman for those behaviors that flow naturally from compassion, and speaking out against those which cannot be countenanced if they cause danger and pain to others. Shaw did find a way to stop reacting and learned the deeply meaningful joy of responding in the context of Simple Reality.

What about the rest of us? Are we finding the courage to look at our dysfunctional behaviors? Why do we persist in driving while texting, for example? “Richtel tries out several analogies to describe the rush we get from a phone: alcohol, drugs, television, video games, junk food, the fight-or-flight response [reaction] to a tap on the shoulder … Our bodies love the little hit of dopamine we get each time we check our phones for something, anything.”

It’s been a few years since Reggie Shaw found way to cope with the guilt, shame and regret experienced by his false self. Had he been supported by an understanding of the structure of his own consciousness (story determines identity and identity drives behavior), he might have had a better chance of finding the “heaven on earth” promised by the Gospel. Instead, like most of us, he has probably returned to the beliefs, attitudes and values of P-B wherein compassion is discouraged.

____________________________________________________________

References and notes are available for this essay.

Find a much more in-depth discussion in the Simple Reality books:

Where Am I? Story – The First Great Question

Who Am I? Identity – The Second Great Question

Why Am I Here? Behavior – The Third Great Question

Science & Philosophy: The Failure of Reason in the Human Community